The mechanical failure of abutment screw connections in full-arch implant-supported prostheses represents one of the most prevalent and challenging complications encountered in implant dentistry. While screw loosening occurs in approximately 7.2% of implant prostheses overall, the rates vary substantially based on design parameters and clinical context [1]. Unlike single-crown restorations that benefit from localized stress distribution, full-arch prostheses present unique biomechanical challenges stemming from the complex interplay between multiple implant positions, cantilever extensions, occlusal forces, and the cumulative effects of preload loss across numerous screw joints [1].

The clinical significance of this complication is well-established, yet the underlying etiology remains multifactorial. It involves mechanical principles of preload maintenance, the inevitable settling effect that occurs at component interfaces, the biomechanical consequences of implant angulation in full-arch designs, and the paradigm shift in understanding crown height space (CHS) as a more critical design variable than traditional crown-to-implant ratios [8], [11]. This analysis synthesizes current evidence regarding why multi-unit abutment (MUA) screws progressively loosen in full-arch cases, examines the biomechanical mechanisms that distinguish these systems from simpler single-crown restorations, and establishes evidence-based prevention protocols to minimize mechanical complications.

Contents

- Epidemiology of Screw Loosening in Full-Arch vs Single-Crown Restorations

- Preload Dynamics and the Settling Effect in Multi-Unit Assemblies

- Material Science: Titanium Grade 4 vs Grade 23

- Angulation Effects on MUA Screw Joint Stability

- Crown Height Space and Non-Axial Loading: Paradigm Shift from Crown-to-Implant Ratio

- Clinical Prevention Protocols: Torque Specifications and Maintenance Intervals

- Failure Mode Differentiation: Reversible Loosening vs Screw Fracture

- Conclusion

- References

Epidemiology of Screw Loosening in Full-Arch vs Single-Crown Restorations

The incidence and temporal patterns of screw loosening in full-arch implant prostheses differ substantially from single-tooth restorations. In a large clinical cohort of 1,928 implants with follow-up periods up to 70 months, screw loosening occurred in 7.2% of all implants. However, disaggregating the data by prosthesis design reveals a striking divergence: single crowns demonstrated screw loosening rates of 14.0%, substantially higher than the 3.8% rate observed in splinted crowns [1]. This approximately 3.7-fold difference underscores a fundamental principle: the distribution of forces across multiple implants and the bracing effect of splinting dramatically reduces the shearing forces and moment loads that concentrate on individual screw joints [1], [2]. Clinically, splinted crowns demonstrated an odds ratio of approximately 0.271 compared with single crowns, effectively a 73% reduction in loosening risk.

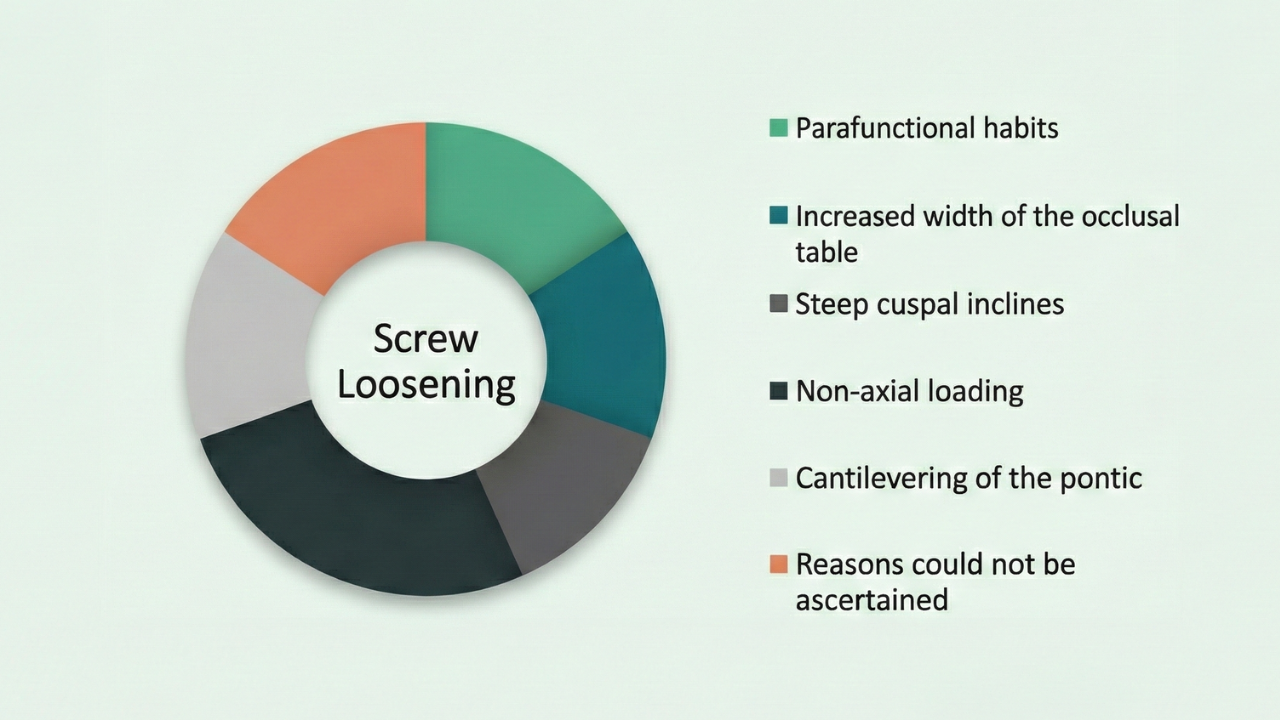

Figure 1. Distribution of contributing factors to abutment screw loosening in single crowns: parafunctional habits, increased occlusal table width, steep cuspal inclines, non-axial loading, and pontic cantilevering. These factors remain relevant in full-arch cases where they manifest across multiple implant positions. Source: Londhe SM et al., J Int Clin Dent Res Organ 2019; PMC6994738

Despite the protective effect of splinting, the temporal distribution of loosening events in full-arch cases reveals a critical vulnerability in the immediate post-loading phase. Among all cases of screw loosening, 50.4% occurred within six months of loading, with 71.3% of all incidents manifesting within the first year [1]. This temporal concentration suggests that the settling effect and initial preload loss—phenomena most pronounced immediately after torque application—drive early screw loosening rather than progressive fatigue failure. Furthermore, 22.3% of patients who experienced screw loosening developed recurrent loosening, indicating that the initial occurrence often reflects an uncorrected biomechanical pathology. Anatomical location significantly influences risk, with the molar region demonstrating the highest incidence. Screw loosening frequency in the molar region is 8.5%, compared to 6.9% in the anterior region and 3.8% in the premolar region [1]. In full-arch cases, where distal implants are frequently positioned in the molar zone to minimize cantilevers, these sites become the primary points of failure. The concentration of occlusal forces in the posterior region creates larger moment loads; when combined with the distal positioning typical in full-arch on 4 and 6 implant protocols, the distal MUA screw becomes the “weak link” in the prosthetic chain.

Table 1: Comparative Incidence of Screw Loosening

| Variable | Single Crown Restoration | Splinted Full-Arch Restoration | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loosening Incidence | 14.0% | 3.8% [1] | Splinting provides a protective bracing effect (OR ~0.27). |

| Temporal Pattern | Distributed over time | 50.4% within 6 months | Early settling effects dominate full-arch failure modes. |

| Recurrence Rate | Variable | 22.3% | Initial loosening often signals persistent biomechanical error. |

| High-Risk Zone | Molar (12.3% in single units) | Distal MUA positions (Molar 8.5%) [1] | Posterior occlusion requires reduced table width. |

Preload Dynamics and the Settling Effect in Multi-Unit Assemblies

Preload, the clamping force generated when a screw is tightened, is the foundation of screw joint stability [3]. However, the conversion of applied torque to preload is inefficient. Approximately 90% of the applied rotational energy is consumed by friction between the thread surfaces and the screw head seating, leaving only 10% to generate actual axial preload [6], [19]. For a standard 35 Ncm torque application, only ~3.5 Ncm effectively creates clamping force. This inefficiency makes the system highly sensitive to surface micro-roughness and lubrication status.

The “settling effect” (embedment relaxation) represents the most significant threat to preload maintenance in the immediate post-operative period. Because machined surfaces contain microscopic irregularities, the initial torque application results in contact primarily at high points (asperities) [3], [6]. Within seconds to minutes of tightening, these high points undergo plastic deformation, allowing the surfaces to settle closer together. This settling reduces the screw elongation that generates clamping force, resulting in a preload loss of 2% to 10% almost immediately [3]. Under cyclic loading, torque loss can escalate to 16.1%–39% [6].

Embedment Relaxation and Surface Micro-Roughness

In full-arch prostheses, the settling effect is cumulative across multiple abutments. In vitro investigations of internal connection implants reveal that removal torque values drop significantly below insertion torque immediately after tightening, purely due to settling. For example, a mean insertion torque of 30.5 Ncm may yield a removal torque of only 27.7 Ncm (9% loss) before any functional loading occurs [3]. This phenomenon necessitates strict retightening protocols. A single torque application leaves the prosthesis vulnerable to immediate loosening as the settling process erodes the initial clamping force.

Retightening Protocols: Timing and Technique

Quantitative data supports specific retightening strategies to counteract settling. A “10-minute wait” protocol—torquing, waiting 10 minutes for settling, and retorquing—has been shown to recover significant preload [3]. More recent investigations into the “Method B” protocol (torque to target, loosen, and immediately retorque) demonstrated a 21.58% increase in immediate stability and a 44.87% increase in long-term stability compared to single-torque methods [21]. This suggests that the mechanical act of smoothing surface irregularities through an initial tightening cycle is more critical than the specific time interval. For full-arch cases, where passive fit is rarely perfect, this protocol helps negate the initial relaxation of the screw joint.

Figure 2. Comparative analysis of screw-tightening protocols: Method B (torque-loosen-retorque) demonstrates 21.58% improvement in immediate stability and 44.87% enhancement in long-term preload retention versus single-torque application. Source: PMC10805556

Material Science: Titanium Grade 4 vs Grade 23

The material composition of the prosthetic screw is equal in importance to the torque protocol. However, “strength” is a complex property; Grade 4 actually possesses higher hardness and resistance to direct compressive pressure. But for screw fixation, where elasticity and resistance to bending/stretching (tensile forces) are paramount, other alloys offer more advantageous properties.

- Grade 4 Titanium (Pure): Excellent hardness and biocompatibility, but rigid. Its lower elasticity limits its ability to flex under the non-axial loads typical of full-arch prostheses without risking irreversible deformation.

- Grade 5 Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V): An alloy offering improved mechanical properties for dynamic loading compared to Grade 4, specifically in terms of fatigue resistance.

- Grade 23 Titanium (Ti-6Al-4V ELI): “Extra Low Interstitial” grade is the material of choice for premium systems like XGATE. It offers the best balance for screw fixation—high fatigue strength combined with superior ductility and elasticity (lower modulus of elasticity).

Figure 3. XGATE implant system components are manufactured from Titanium Grade 23 (Ti-6Al-4V ELI). Compared to commercially pure titanium, this alloy demonstrates superior performance under bending and tensile forces due to its capacity for elastic deformation—returning to its original geometry after loading. This property is critical both during screw thread preloading and under multidirectional masticatory forces, minimizing the probability of screw loosening and fracture.

The “elastic memory” of Grade 23 titanium allows the screw to elongate within its elastic limit during tightening and functional loading. In full-arch prostheses, where the framework exerts constant bending moments, this capacity to stretch and rebound without permanent deformation is critical for long-term joint stability.

Angulation Effects on MUA Screw Joint Stability

The biomechanics of full-arch rehabilitation often necessitate the tilting of distal implants to reduce cantilever length. While advantageous for bone utilization, angulation introduces off-axis loading that compromises screw stability. A landmark 2025 in vitro study specifically isolated the variable of MUA angulation, comparing straight (0°) controls against angulated abutments under cyclic loading.

XGATE V-Type: The Straight “Savior”

The XGATE V-Type Multi-Unit Abutment is a straight component with a screw-passive multi-part design (MUA body + sleeve + retentive screw) engineered for simplicity and strength. However, its unique ultra-low profile design offers a profound clinical advantage: it can accommodate implant divergence of up to 40° between implants. This allows clinicians to use a simple, robust straight abutment even in cases with significant conversion, often negating the need for complex angulated components entirely. For many “borderline” cases, the V-Type is a savior, simplifying the prosthetic path and reducing the mechanical burden on the screw joint.

Figure 4. The XGATE V-Type abutment design allows for the compensation of significant implant divergence (up to 40° between implants) using a straight one-piece component, often eliminating the need for multi-component angulated abutments in moderately divergent cases.

XGATE D-Type: Mastering the Angle

When angulation exceeds the capacity of straight components, the XGATE D-Type Multi-Unit Abutment is essential. Available in 17°, 30°, and 45° angulations, it allows for the correction of severe divergence, enabling the use of available bone in even the most atrophic maxillae. While increasing angulation inherently increases the load on the screw joint, the D-Type system mitigates this via two critical mechanisms:

Figure 5. XGATE angulation solutions. When divergence exceeds the capacity of the straight V-Type, the D-Type system provides correction at 17°, 30°, and 45° to manage severe atrophy and off-axis placement, protecting the prosthesis from “system-level” failure.

- Elasticity is Key: Because angled abutments are subjected to intense bending moments, the use of Grade 23 titanium screws with superior elasticity is non-negotiable. This facilitates the absorption of micro-movements without fracture.

- The “Lesser Evil”: While angulated abutments introduce mechanical stress, they are a strategic compromise. It is biomechanically preferable to risk a screw fracture—which is retrievable and replaceable—than to risk the implant-bone interface due to excessive cantilevers. The D-Type abutment acts as a “fuse,” protecting the osseointegration from catastrophic overload.

Cantilever Length vs Implant Inclination

The trade-off between angulation and cantilever length is a central treatment planning dilemma. Finite element analyses suggest that “cantilever influence is greater than implant inclination” regarding stress distribution [54]. In full-arch restoration configurations, tilting distal implants to 30° or 45° significantly reduces stress on the peri-implant bone by shortening the cantilever, provided adequate anterior-posterior (A-P) spread is achieved [29], [54]. However, this bone-level benefit comes at the cost of prosthetic screw strain. A 45° tilt with frontal loading can generate cortical stresses up to 265 MPa, compared to 95 MPa at 15° angulation [29]. Therefore, while angulation protects the bone by reducing cantilevers, it transfers the stress burden to the MUA screw, necessitating the use of high-strength alloys (Grade 23) and strict torque protocols.

Figure 7. Anterior-posterior spread measurements across full-arch restoration configurations demonstrating increased implant distribution in five-implant designs for enhanced load distribution. Source: Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2023

Figure 8. Distal implant configurations at 15°, 30°, and 45° angulations with corresponding bar framework arrangements. FEA analysis demonstrated cortical stresses of 95 MPa at 15° versus 265 MPa at 45° angulation under frontal loading. Source: Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology 2025

Table 2: Angulation Impact on Screw Stability

| Parameter | Straight MUA (0°) | Angulated MUA (17°) | High Angulation MUA (30°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Torque Loss (Post-Cycling) | Baseline (Control) | 16.43% – 23.53% | Significantly Higher (p=0.01) |

| Screw Deformation | 0% | Minimal | 100% Incidence [31] |

| Primary Failure Mode | Coping Debonding | Loosening | Screw Deformation/Fracture |

Crown Height Space and Non-Axial Loading: Paradigm Shift from Crown-to-Implant Ratio

Traditional prosthodontic metrics emphasized the Crown-to-Implant Ratio (CIR). However, contemporary evidence supports a paradigm shift toward Crown Height Space (CHS) as the primary predictor of marginal bone stress and screw loosening [8], [11]. Finite element studies demonstrate that when CIR is manipulated by lengthening the implant (maintaining CHS), stress values remain static. Conversely, increasing CHS—regardless of implant length—exponentially increases marginal bone stress and screw joint strain [8].

The biomechanical threshold for CHS appears to be 12–15mm. When CHS exceeds 15mm, the lever arm created by the prosthesis magnifies lateral forces to such a degree that standard implant distributions may be insufficient. A 12-degree off-axis force applied to a 20mm crown height increases lingual and apical moment forces by 200% compared to a 10mm crown [33]. In atrophic ridges where CHS often exceeds 15mm, the solution is not longer implants, but more implants to distribute the magnified moment loads.

Occlusal table width acts as a force multiplier in these scenarios. Clinical data indicates that 15.38% of screw loosening cases are directly associated with wide occlusal tables [36]. A wider table increases the cantilever arm from the central axis of the implant to the cusp tip. Consequently, narrowing the occlusal table by 1–2mm and reducing cuspal inclination (flattening the occlusion) are critical design strategies to reduce the torque applied to the MUA screw [22]. Furthermore, bruxism amplifies these risks, with bruxers exhibiting a 2.2 to 4.7-fold increase in failure risk [46].

Clinical Prevention Protocols: Torque Specifications and Maintenance Intervals

The discrepancy between manufacturer specifications and clinical reality is a primary source of MUA screw loosening. Often, the culprit is not torque application, but manufacturing precision. Many manufacturers produce components with large tolerances, leading to poor fit at the hexagon or conical interface. When the fit is loose (tolerances >0.05mm), even a calibrated torque wrench cannot guarantee a stable, preload-maintaining connection.

While standard MUA torque recommendations range from 20 to 35 Ncm, manual tightening introduces dangerous variability. Studies comparing hand tightening versus calibrated torque wrenches reveal that hand tightening results in a standard deviation of 6.51 Ncm, with values ranging from 27 to 43 Ncm. The upper limit of this range (43 Ncm) approaches the plastic deformation threshold of many prosthetic screws, risking immediate damage. In contrast, calibrated torque wrenches reduce variability to a standard deviation of 2.47 Ncm, ensuring preload remains within the optimal therapeutic window [13].

Torque Delivery: Calibrated Instruments vs Manual Tightening

To ensure consistent preload generation, clinicians must utilize calibrated instrumentation alongside high-precision prosthetic components. The XGATE Prosthetic Screw System is engineered to support this precision using Grade 23 titanium with ultra-low tolerances. XGATE components are manufactured with interface tolerances of no more than 0.02 mm. This microscopic precision ensures optimum friction coefficient and contact area, meaning that a significantly higher percentage of applied torque is converted into actual preload rather than being lost to friction or movement within a loose interface.

Maintenance Recall: Evidence-Based Intervals

The maintenance phase is critical for detecting early preload loss. Given that 50% of loosening events occur within the first six months [1], a strict recall interval of 2 to 6 months post-delivery is mandated. However, the American College of Prosthodontists (ACP) advises against routine retightening of screws that show no clinical signs of loosening, as this may lead to excessive screw elongation [18]. Instead, the protocol should involve verifying stability; if a screw is loose, it must be replaced rather than simply retightened, as the loosening event likely induced fatigue damage.

Table 3: Torque Application Variability

| Method | Torque Variability (SD) | Torque Range (Ncm) | Clinical Risk |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hand Tightening | 6.51 Ncm | 27 – 43 Ncm | High risk of over-torquing (fracture) or under-torquing (loosening). |

| Calibrated Wrench | 2.47 Ncm | 28 – 35 Ncm [13] | Consistent preload generation; 62% reduction in variability. |

Failure Mode Differentiation: Reversible Loosening vs Screw Fracture

Differentiation between reversible loosening and catastrophic fracture is essential for prognosis. Screw loosening is theoretically reversible, yet it serves as a precursor to fracture. The correlation between microleakage and loosening (r=0.65) suggests that bacterial infiltration often accompanies the loss of preload, potentially acting as a diagnostic marker [40].

Fracture rates are generally low (0.5% to 2%) but rise significantly in the presence of undetected loosening [26]. The progression from loosening to fracture is driven by fatigue; a loose screw is subjected to bending forces it was not designed to withstand. Notably, internal conical connections demonstrate lower loosening rates (1.3%) compared to external hex designs, but when failure occurs in angulated scenarios (30°), screw deformation is nearly guaranteed (100%) [25], [31]. This “system-level collapse” occurs when the failure of a single screw redistributes loads to adjacent implants, causing a cascade of loosening events that can compromise the entire framework [24].

Figure 10. 3D rendering of three implant-abutment connection designs: (A) External Hexagon, (B) Internal Hexagon, (C) Cone Morse, with longitudinal cross-sections. Internal conical (Morse) connections demonstrate lowest loosening rates (1.3%) compared to external hex designs. Source: PMC9311948

Figure 11. Clinical photograph demonstrating simultaneous fracture at the abutment neck and central screw location in a Morse taper connection. Indexed abutments showed higher fracture incidence than non-indexed designs due to stress concentration at the positioning index. Source: PMC9796380

Conclusion

The etiology of MUA screw loosening in full-arch prostheses is a deterministic process driven by specific biomechanical thresholds rather than random chance. While splinting reduces the overall risk compared to single crowns, the severity of the complication in full-arch cases is magnified by the settling effect, high angulation, and excessive crown height space. The data indicates that 30° angulation represents a critical tipping point for screw deformation, and that CHS >15mm requires a fundamental change in implant number rather than reliance on prosthetic compensation.

Prevention requires a rigid adherence to protocol: the use of calibrated torque wrenches to eliminate the 43 Ncm risk of hand tightening, the implementation of retightening protocols (Method B) to negate the 10% settling loss, the use of high-elasticity Titanium Grade 23 screws, and the design of prostheses with narrowed occlusal tables to minimize moment arms. By respecting these biomechanical realities, clinicians can maintain the integrity of the multi-unit assembly and ensure long-term prosthetic survival.

References

- Lee KY, et al. (2020). Clinical study on screw loosening in dental implant prostheses. Journal of Advanced Prosthodontics. NIH/PubMed. PMID: 32222622

- Everts J, Everts B, et al. (2010). Comparison of strains for splinted and nonsplitted screw-retained implant crowns. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. PMID: 22167421

- Vinhas AS, et al. (2023). In vitro study of preload loss in different implant abutment connections. PMC. PMC8879145

- Kallus T, Bessing C. (1994). Loose gold screws frequently occur in full-arch fixed prostheses supported by osseointegrated implants after 5 years. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 9(2):169-178. PMID: 8206552

- Comparison of stress distribution around splinted and nonsplinted implant-supported crowns. Journal of Prosthodontics, 13(2):109-115.

- Pardal-Peláez B, Montero J. (2017). Preload loss of abutment screws after dynamic fatigue in single implant-supported restorations. Acta Odontológica Latinoamericana.

- Stress assessment of abutment-free and three implant abutment connections. PMC, 2024. PMC12565274

- Ferreira JJR, et al. (2021). Effect of crown-to-implant ratio and crown height space on marginal bone stress. PMC. PMC8408299

- Photoelastic stress analysis in prosthetic implants of different diameters. PMC, 2014. PMC4225983

- Stress distribution on the components of multi-unit abutment with different abutment angulations. CNCB.

Show full reference list (54 sources)

▼

- Crown-Height Space Guidelines for Implant Dentistry—Part 1. (2024). ICOI Consensus Conference.

- Photoelastic analysis of stress distribution on parallel and angled implant abutments. ResearchGate.

- Kharbi NI, et al. (2021). Tightening torque of implant abutment using hand drivers versus torque wrench. PMC. PMC7335033

- Management of fractured abutment screws. Resnik Implant Institute.

- Implant maintenance: A clinical update. PMC, 2015. PMC4897104

- The science of torque: Why precision matters in implantology. OEMDent.

- The effects of laboratory contamination of implant abutment screw reverse torque values. PMC, 2024. PMC12440296

- Position statement: Maintenance of full-arch implant restorations. American College of Prosthodontists.

- Effect of the coefficient of friction and tightening speed on the preload of an abutment screw. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 113(5):405-411.

- Management of abutment screw loosening: Review of literature and case reports. PMC, 2015. PMC4148504

- Influence of abutment screw-tightening methods on the screw joint stability. PMC, 2023. PMC10805556

- Evaluation of the occlusal scheme of posterior implant-supported single crowns. IJCMPH, 2023.

- Abutment screw loosening in implants: A literature review. PMC, 2021. PMC7842481

- Impact of mechanical complications on success of dental implant supported prostheses. PMC, 2022. PMC8890925

- Abutment mechanical complications of a Morse taper connection implant system. PMC, 2022. PMC9796380

- Loosening and fracture of original versus non-original abutment screws. Universidad Europea.

- Symptoms of loose dental implant crown: What to watch for. Crossroads Dental.

- Internal hexagonal implants versus external hexagonal implants versus Morse taper. Revista FT.

- Effects of distal implant and occlusal load angulation using finite element analysis. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2025.

- The effect of digital manufacturing technique on implant abutment connection misfit and preload. PMC, 2022. PMC8891687

- The influence of multi-unit abutment angulation on prosthetic screw-joint stability. Journal of Prosthodontics, 2025. PMID: 41273756

- Effect of crown dimensions on stress distribution in implant-supported prostheses. Iranian Journal of Dental Research.

- Crown-height space guidelines for implant dentistry. ICOI, 2024.

- Determination of fatigue life of titanium alloys used as locking screws. IJNES, 2017.

- Passive fit in screw retained multi-unit implant prosthesis. PMC, 2014. PMC3935037

- Factors associated with abutment screw loosening in single implant crowns. PMC, 2019. PMC6994738

- Titanium implants with high biocompatibility. Sigma-Aldrich.

- The fit of implant framework: A literature review. Saudi Journal of Dental Research.

- Risk factors associated with screw loosening in CAD-CAM custom abutments. Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry, 2023.

- Systematic analysis of factors that cause loss of preload in dental implants. PMC, 2018. PMC6070846

- Bacterial microleakage at the implant-abutment interface. PMC, 2022. PMC9311948

- Outcomes and complication rates of tooth-implant-supported fixed prosthesis. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 2020. PMID: 32724920

- Biomechanical implant treatment complications: A systematic review of clinical studies. International Journal of Oral & Maxillofacial Implants, 2012. PMID: 22848892

- The influence of implant-abutment connection on the screw loosening torque. Springer Medizin, 2018.

- Meta-analysis of failure and survival rate of implant-supported prostheses. PMC, 2014. PMC4589703

- Bruxism in implant-supported rehabilitations: A narrative review. PMC, 2024. PMC12512445

- Comparison of different implant-supported fixed prostheses designs. SCIRP, 2024.

- Principles for abutment and prosthetic screws and screw-retained components. Pocket Dentistry.

- Bruxism: Its multiple causes and its effects on dental implants. Craniofacial Journal, 2014.

- Effect of thermodynamic cyclic loading on screw loosening of dental implants. Frontiers, 2023.

- Internal hex implants: Understanding the connection and the inward migration phenomenon. Dental Master Med.

- Biomechanical analysis of All-on-4 implant supported framework with cantilever. PMC, 2024. PMC11992848

- Influence of connection geometry on dynamic micromotion at the implant-abutment interface. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 2007. PMID: 18069372

- Biomechanical comparison of all-on-4 and all-on-5 implant-supported prostheses. Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology, 2023.

Disclaimer: Any medical or scientific information provided in connection with the content presented here makes no claim to completeness and the topicality, accuracy and balance of such information provided is not guaranteed. The information provided by XGATE Dental Group GmbH does not constitute medical advice or recommendation and is in no way a substitute for professional advice from a physician, dentist or other healthcare professional and must not be used as a basis for diagnosis or for selecting, starting, changing or stopping medical treatment.

Physicians, dentists and other healthcare professionals are solely responsible for the individual medical assessment of each case and for their medical decisions, selection and application of diagnostic methods, medical protocols, treatments and products.

XGATE Dental Group GmbH does not accept any liability for any inconvenience or damage resulting from the use of the content and information presented here. Products or treatments shown may not be available in all countries and different information may apply in different countries. For country-specific information please refer to our customer service or a distributor or partner of XGATE Dental Group GmbH in your region.